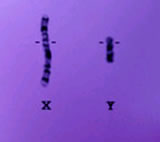

Y chromosome sequence completedDNA readout reveals genetic palindromes

safeguard male-defining chromosome.

19 June 2003

JOHN

WHITFIELD

|

| The Y chromosome has sex

with itself to guard against mutation. |

| ©

GettyImages | | |

Reports of the demise of the Y chromosome and an

impending extinction of men may have been exaggerated.

The Y's full genome sequence reveals that we have

underestimated its powers of self-preservation.

Instead of doubling up to protect its genetic cargo

like other chromosomes, the lone Y safeguards its genes

by having sex with itself, an international consortium

has found.

"We're on a quest to bring respectability to the Y

chromosome," says geneticist David Page of the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, leader of the

sequencing team. The male-defining chromosome was

previously thought of as a wasteland where genes go to

die.

The Y's defences are double-edged, however, sometimes

leading to infertility. The sequence should help us to

diagnose and treat such genetic mishaps.

Two-way street

Human chromosome pairs swap genes to minimize bad

mutations. Y, which has no partner, faces being whittled

away by mutation. Some estimate that the chromosome

could be complete junk in about ten million years.

The finished sequence shows that the chromosome

fights entropy with palindromes. About six million of

its 50 million DNA letters reside in sequences that read

the same, in opposite directions, on both strands of the

double helix. The longest is nearly three million

letters long1.

"The Y chromosome is a hall of mirrors," says Page.

These palindromes house many genes - which means that

there is a copy at each end of the palindromic sequence.

These provide back-ups should harmful mutations arise.

The mirror-image structure also allows the arms to swap

position when DNA divides. Genes are shuffled and bad

copies are purged.

|

| There are 50 million

letters in Y's finished sequence. |

| source:

Nature | | |

Page's team has calculated the amount of swapping

needed in each generation to produce the near-perfect

palindromes of the human Y. They estimate that every

man's Y contains 600 DNA letters that differ from his

father's2.

This is thousands of times more than the normal mutation

rate.

"No one had contemplated that there would be this

level of gene conversion in our own genome," says

Huntington Willard of Duke University, Durham, North

Carolina. "It gives us a glimpse of how the Y has

protected itself."

Other researchers see swapping as an evolutionary

accident, not a safeguard. "It's a daring suggestion,

but I find it a bit difficult to believe," says

geneticist Mark Jobling of the University of Leicester,

UK.

Jobling is sceptical because the trick has a high

cost: good genes are just as liable to be lost as bad.

This is a major cause of male infertility, as most of

the genes within the palindromes control testes

development. One in every few thousand men is infertile

because key genes have been deleted.

Y files

Genetic testing is already used to diagnose male

infertility. A fuller understanding of the Y's make-up

will help refine these tests, and improve doctors'

advice to couples. "We have a greater knowledge of where

the Y tends to break," says Page. "Testing needs to be

updated to reflect our better understanding from the

finished sequence."

The palindromes, and other forms of repeated DNA,

made the Y chromosome very tricky to sequence. So the

finished sequence comes from just one man's Y. Getting

more sequences is essential, says Jobling, as the

chromosome's structure, and hence biology, varies

greatly around the world.

"We have a beautiful snapshot of the Y chromosome,"

he says. "Now we need to look in other lineages to build

up a photo album of its diversity." |